|

|

|

|

| |

|

History of Art is the most important criterion for

a valid artistic evaluation. Art does not tolerate

regression or repetition. An inherited literary

expression of so-called poetic words is not poetry even if it pleases, just like skillfully drawn lines do not necessarily make a painting, simply because art is not mere aesthetics.

Art is a word of doubts and hues, and therefore, a subtle science that brings a most relevant contribution to the progress of humanity.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

The preponderant role of spontaneity in Art has been pointed out by the

Surrealists in the 1920’s and emphasized later by Georges Mathieu, the French

painter and the theorist of the Lyrical Abstract movement in France. It does not

need any further demonstration. But, whereas the Surrealists gave to

automatism in Art a psychological interpretation, Georges Mathieu, an admirer of

Pollock and Wols, gave it a phenemenological interpretation. No one has ever

asked himself whether a stone has a meaning or if it represents anything outside

itself. On the contrary, everybody has always been satisfied with confirming its

existence in Nature and studying its structure. A work of art looms up in the world

as a sign without denotation, and its essence had to be searched for in the act of

creation itself.

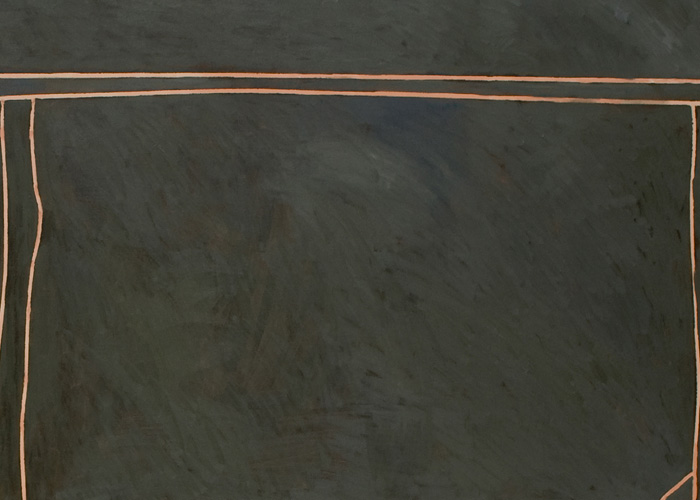

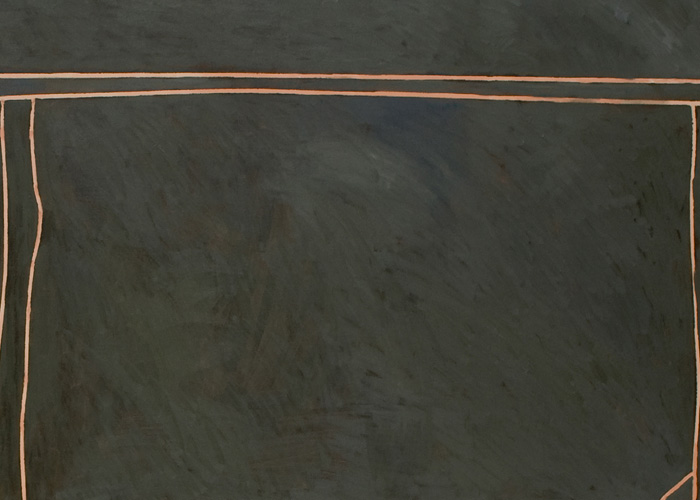

In spite of what its defenders may claim, pure spontaneity always runs the risk of

being uncontrolled and resulting in gratuitous graffiti. Therefore, there is a need

of articulating the rational and the intuitive in Art. This is the main reason why my

work consists of a simple and solid structure, on which a spontaneous gesture is

permitted. These gestures have a double function: they add a lyrical dimension to

the dryness of the structural framework and they define the path of the future

search for structures. The interpenetration of the two planes creates an intended

tension of forms.

An artist cannot be defined without referring to his work. The painter does not exist

anywhere but in his painting. As he creates, his creation in turn creates and

transforms him. Artistic creation is a patient and passionate elaboration of the self.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Picasso’s father, although an artist himself and a drawing professor, became once so

aware of the virtuosity and talent of his adolescent son, that he handed over to him

his palette and his brushes, and gave up painting.

I cannot understand such an attitude, where Art is apprehended as a rivalry and

contest among artists. The Other does not exist in the process of creation and

therefore, the recognized virtuosity of one artist cannot prevent another from

creating.

Art is an intimate act where one obeys, in the humility of his solitude, an inner need.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

Artists search for a truth. We have all made, or heard someone make, a similar

statement at one time or another; we may have also read it in a newspaper, a

magazine or a book. In our minds we have capitalized these words and we have given

them a rather Platonistic interpretation, thus perceiving art works as the shivering

shadows of a transcending Truth. We have believed in the existence of an Absolute in

Art, which artists may attempt to reach, and which they actually do reach at various

degrees, which degrees allow us to differentiate between true artists and false ones,

between great artists and ordinary ones. This kind of understanding of Art leads us

unmistakably to the belief that artists have always pursued one and the same goal.

In reality, artists have not repeated themselves over the years. Painting, for instance,

like any other artistic expression or any product of the human intellect for that matter,

evolves through its own mechanisms of development. History may repeat itself, but

History of Art or the History of Ideas does not allow repetitions or redundancies. Each

artwork has to be placed somewhere in Time within which it was created. As Kandinsky

wrote, “art is the child of its time and quite often the mother of our feelings.” An

artwork has to state problems, find answers based on previous artistic knowledge, and

finally become itself a basis for future developments and research. In other terms, an

artwork is like a loop in a chain: it exists only between two others; any loop outside that

chain is condemned to be lost and forgotten. Producing or understanding an artwork

needs this awareness of the historical aspect of artistic creation. Each work of art has

to be diachronically justifiable. This historical significance is the first criterion for a sound

artistic judgment. However, for a artwork to be acceptable, its place in History is a

necessary but insufficient condition. After complying with the diachronic justification, it

has to satisfy some synchronic considerations: how does an artist assert his/her identity,

and most importantly, how does the artist develop his/her own expression.

History of Art, during the first half of the 20th century, has witnessed the blooming of

several theories in representational painting, which were the late developments of the

artistic movements of the 19th century: some tried to develop impressionism, others had

more affinities with the VanGoghian expressionism; the Cubists, who developed Cézanne

on a strictly formalistic level, remained fundamentally figurative. However, after Matisse,

there is no convincing thesis in representational painting. Even the deformed figures of

the British expressionist Francis Bacon are integrated in an abstract pictorial space, which

makes it impossible to describe his art as purely representational. Kandinsky, Klee,

Mondrian and others, who can be related to Cézanne on a spiritual level rather than

formalistic, have developed abstraction as a means of expression, which started in the

early years of this century, but really flourished in he 1940’s in Europe as well as in the

United States. Since then, only abstract artists, especially those of the American School,

seem to be convincing enough to be considered the standards of today’s painting.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

A painting hanging on a wall is like a window open to the world, which, depending on the

artist’s standpoint, affords either a view of the outside or a view of the inside. A painting

with a view of the outside, mostly when it is abstract, becomes infallibly a landscape by

assimilating its rhythms and colors. A landscape is a meditation over the visible world,

and in that sense, Richard Diebenkorn, for example, is a landscape artist. Indeed, his

naming of the body of his abstract work since the mid-sixties by the unique title of “Ocean

Park” is not a fortuitous decision: besides being the name of a street in Santa Monica

where he resides, the two words that form the title can only impel our minds to wander into

vast spaces where the greens, the blues and the grays abound. Critics used to describe

Monet as an “eye”: that is undoubtedly the essential quality of a landscape artist. The eye

is but the observer of the outside world. A painting with a view of the inside, however, is

the product of a mind that meditates upon itself. Such a painting is either introspective or

mystical; Arshile Gorky, for instance, was introspective in nature, rather nostalgic and

agonizing, and his pathos, which lies in the graphic element of his paintings, only revives

ghosts from beyond; the works of Rothko, on the other hand, have the mysterious and

austere obsessiveness, yet comforting presence of a prayer.

I sense in myself a strong urge to destroy by all means any velleity of cultivating the

landscape for no other reason than its attractive aesthetics, and feel predisposed towards

intimate dialogues with myself and the artwork. The choice of colors and compositions is

guided by a willingness to avoid provoking, by a set of connotations of shapes and colors,

bursts of images of even sensations of landscape in the mind of the receiver of the

message, making the artwork a bare reasoning over the self, and the artistic experience

one of rationality.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

|